Bigger Trucks: Bad for the Environment

Policymakers are tasked with addressing severe environmental problems that are central to climate change. Transportation is the largest contributor of greenhouse gases, and within the freight sector, trucking represents the majority of harmful emissions. A major issue surrounding transportation policy is the most efficient way to move freight and the goods people need in their everyday lives, with some calling for longer and heavier trucks as the solution. Proposals include increasing the weight limit of trucks from 80,000 pounds to 91,000 pounds and the length of double trailers from 28 feet to 33 feet, also known as “double 33s”. As we work towards addressing climate change, allowing bigger trucks would represent a significant step backwards.

Proponents of these bigger trucks claim significant environmental benefits but rely on the false premise that bigger trucks mean fewer trucks. This simplistic view ignores the complex dynamics of shipping rates and shipper choices. Once accounted for, we see a dramatic shift of both intermodal and carload freight away from the rails to our roads. In terms of both fuel use and emissions, rail is far more environmentally friendly on a ton-mile basis.[1]

Recent research on the subject found that proposals for bigger trucks could lead to an increase of as much as 600 billion ton-miles of truck traffic, resulting in an additional 4.27 billion gallons of fuel burned and 55.58 million tons of carbon emissions.

Diversion

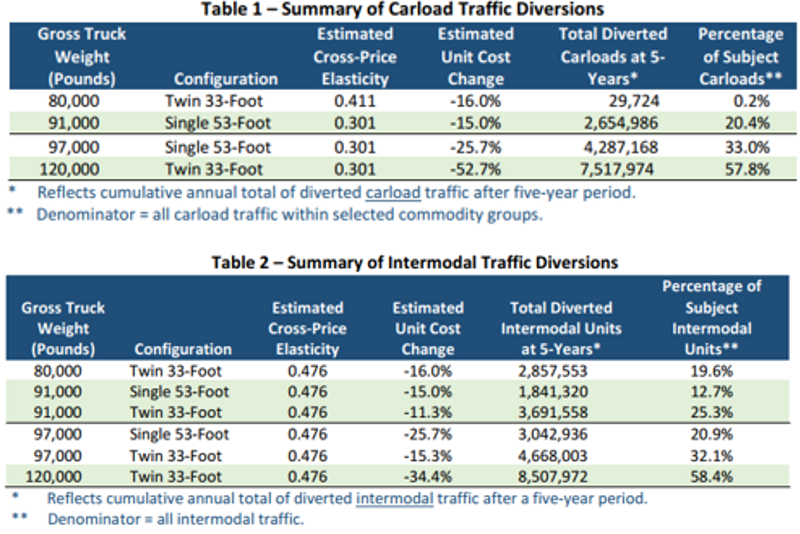

The fundamental issue at hand is that of diversion from other modes of transportation, particularly rail. Increasing truck size and weight shifts the economics of shipping, leading to large amounts of freight diverted from the rails to our roads.

Bigger truck proponents rely on the argument that “bigger trucks mean fewer trucks”, utilizing flawed data from the USDOT that theorized minimal diversion. There are two ways to derive diversion estimates. The USDOT utilized a deterministic model, relying on restrictive assumptions about the relationships between carrier costs, the resulting shipping rates and the choices of shippers. Our research uses actual available data to estimate the responsiveness of modal choice to changes in the price of transportation alternatives. These elasticity estimates are used to simulate the effect on traffic shares under the new rate structure.

Our data-driven econometric estimates identify large amounts of diverted freight associated with proposals allowing double 33s and increasing the national weight limit to 91,000 pounds.[2]

The double 33 foot configuration could cause a 19.6% diversion of intermodal traffic to truck. A weight increase to 91,000 pounds was associated with a 20.4% diversion of carload units and a 12.7% diversion of intermodal loads.

Unlike data used by proponents of bigger trucks, our data relies on an empirical approach utilizing decades of actual pricing, providing a more accurate prediction of shipper responses. Taking this more thorough examination into account, it is clear that bigger trucks do not mean fewer trucks, and in fact lead to a net increase in total vehicle miles traveled by heavy vehicles. The data shows that for the 91,000-pound configuration, total large truck vehicle miles traveled would increase by 17.49 billion, representing a 10.7% overall increase. For double 33s, there would be an increase of 2.18 billion miles in travel by large trucks.

Fuel Use

With more accurate diversion data, we can calculate the amount of fuel needed to haul diverted freight by plugging correct variables into existing USDOT calculations.

Rail transportation is inherently more fuel efficient, averaging 492 ton-miles per gallon[3]. Truck transportation averages 121 ton-miles per gallon.[4]

The resulting fuel use and subsequent emissions by trucks carrying diverted loads is as follows[5]:

| Fuel/Emission Changes by Configuration | 91K | Twin 33 |

| Fuel Change (Billion Gals) | 3.53 | 0.74 |

| Carbon Emissions (Million Tons) | 37.49 | 18.09 |

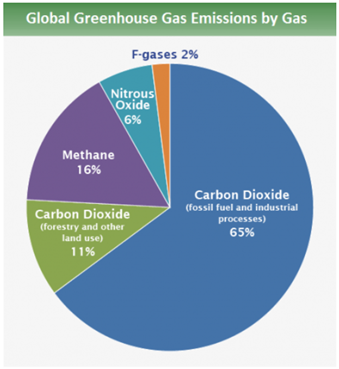

Emissions

Transportation represents the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions by industry[6] and must be at the focal point of our efforts to combat climate change.

The increased emissions stemming from the diversion of freight from our rails to our roads is deeply concerning. A weight increase to 91,000 pound trucks would lead to an additional 37.49 million tons of carbon emissions stemming from truck freight. Adoption of double 33s would result in an additional 18.09 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

Carbon dioxide is responsible for 76% of all greenhouse gas emissions[7] and must be the focus of our efforts to combat climate change.

[1] American Association of Railroads; 2020. Freight Rail and Preserving the Environment.

[2] Mingo, Roger D; December 2020. Another Look at FHWA’s Analysis of Twin 33 and Six-axle Single Combination Vehicles in the 2015 Comprehensive Truck Size and Weight Study

[3] CSX; 2020. The CSX Advantage: Fuel Efficiency.

[4] Bureau of Transportation Statistics; 2020. Combination Truck Fuel Consumption and Travel. Calculation assumes an average 20-ton freight capacity.

[5] Mingo, Roger D; December 2020. Another Look at FHWA’s Analysis of Twin 33 and Six-axle Single Combination Vehicles in the 2015 Comprehensive Truck Size and Weight Study

[6] United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2020. Fast Facts: U.S. Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions 1990-2018

[7] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2014. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change